This Summary was written by Ulrik Løth Holm

The 02.03.22 we held our first SPOTinar of the year called ‘Occupational Therapy in disadvantaged, marginalized and addicted populations with Jacob Madsen.

The SPOTinar had 100 registered students and a total of 58 participants on Zoom.

Jacob Madsen is an Occupational Therapist & Researcher. He had his Ph.D. published in 2017 under the title ‘Underprivileged Citizens’ Use of Technology for Everyday Health Management’ and has since then immersed himself into researching related topics while teaching future occupational therapists at University College of Northern Jutland, Denmark. Jacob met Ann A. Wilcock at an ENOTHE conference in 2006 – and was inspired by her dedication to develop theories and contributing to research by writing books, articles and more. He believes as health professionals it is our duty to act on inequality in health.

Facts about Jacob

- Ph.D., Senior Lecturer

- Reg. OT, Msc.OT.

- Works at the department of Occupational Therapy UCN, Denmark.

- Affiliated researcher at Karolinska Institute, Division of Occupational Therapy, Stockholm, Sweden.

Contents of the SPOTinar

At this SPOTinar Jacob specifies and talks about six different topics based on occupational science research (including his own) and other relevant sources:

- Social inequality in health

- Disadvantaged, marginalized and addicted populations

- Occupational science perspective

- Occupational therapy perspective

- A sociopolitical and situated approach

- A socially and politically responsible discipline

Firstly, he presents the role of different occupational determinants as the determinants of inequality in health.

We have the early determinants that affect social position and health → 1. Early childhood development – cognitive, emotional, and social. 2.Schooling – unfinished schooling and 3. Segregation and the local community.

Then there are the causes of illness which are affected by social position → 4. Income – poverty, 5. Long-term unemployment, 6. Social vulnerability. 7. Physical environment – particles and accidents → which leads us on to 8. Work environment – ergonomic and psychosocial, 9. Health behaviour and 10. Early impairment.

And finally, determinants that affect disease consequences such as 11. The role of health care and 12. The exclusive labour market.

To sum this up – Jacob defines 12 different areas as determinants of inequality in health and this showcases how inequality is a complex matter but nevertheless unavoidable as it focuses on the environment as much as the individual – Jacob later goes on to define this in relation to the situated approach.

Who are the disadvantaged, marginalized and addicted populations?

They consist of cash benefits recipients, unemployed and unskilled workers, and early retirement pensioners. Here there are several common features being that they are out of the job market, low income and no or a short education. At the same time, they have disease with a marked social impact (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, mental illness, strokes, heart diseases, lung cancer and diabetes). Drug abusers being an especially socially disadvantaged group. These people fit into one or more of the 12 social determinants mentioned above.

Their everyday life is characterized by smoking, pain, more contact with health services than the average person, eating habits, lack of sleep, violence, no work – no profit, problems with ADL.

An explanatory phrase for the disadvantaged peoples’ circumstance is ‘Poor life – Poor health’. We relate childhood failure, fragile relationships with children, violence and attempted suicide, sexual problems and abuse, general social problems, the feeling of a used body, abuse-related accidents, and general physical problems to this phrase.

Hereafter Jacob introduces a framework for understanding Social Inequality in Health.

On the left side we have the economic, social, and political structures that directly influence social conditions. On the other side we have political initiatives related directly to health. Health and Social conditions continously interacting with each other – and the line between them representing the phenomenon of occupation being the means for doing/acting within this situation.

An Occupational Science Perspective

Jacob introduces a case about Bjarne – who fits the criteria for several of the 12 determinants of inequality in health. Bjarne spends most of the day on his couch without a job – yet he has dreams of the future that he does not act upon. Thereafter he introduces classic occupational science terms such as occupational engagement, occupational justice, occupational in-justice, occupational deprivation, occupational marginalization, occupational alienation, and occupational apartheid.

A short description of each term:

- Occupational engagement: Full participation in occupations for the purpose of doing what one needs and wants to do, being, becoming who one desires to be, and belonging through shared occupations in communities.[1]

- Occupational justice: Equitable opportunities & resources to do, be, belong & become… And absence of avoidable harm.[2]

- Occupational in-justice: The experience of one or more of the following: occupational- deprivation, -marginalization and -alienation.[3]

- Occupational deprivation: A state of preclusion from engagement in occupations of necessity and/or meaning due to factors that stand outside of the immediate control of the individual.[4]

- Occupational marginalization: Experiences of inequity from being outside the dominant or mainstream discourse and events of everyday occupations in a particular context; invisible, silent, in the edge of privilege and entitlement to occupational opportunities and resources.[5]

- Occupational alienation: Experience devoid of meaning or purpose, a sense of isolation and powerlessness, frustration, loss of control or estrangement from society or self that results from engagement in occupation that do not satisfy inner needs related to meaning or purpose.[6]

- Occupational apartheid: A term used to describe the deliberate political exclusion of some populations from some occupational opportunities and resources.[7]

All the above terms can be used to analyze cases like Bjarne. What is restricting Bjarne from participating in occupations that he finds meaningful?

A sociopolitical and situated approach

Bonnie H. Kirsh describes poverty, discrimination, homelessness, abuse, powerlessness, social exclusion, inaccessibility, inequitability and underfunded services as wicked problems. Our society is dominated by an individualistic perspective – where we focus entirely on individuals. She describes this perspective as being “too narrow and inadequate to meet our mission of meaningful occupational engagement for all. A broader sociopolitical approach is needed to promote an understanding of institutional and systemic inequality that governs peoples’ occupational lives”.

It’s a call for Occupational Therapy to become a more socially and politically responsible discipline as occupational is not an individual issue. Therefore, we need a more socially focused approach to enabling occupation as this is important for health and occupational well-being. A paradigm shift from a focus on health to a focus on rights.

Jacobs then goes on to talk about the unsustainability of occupation-based model diagrams such as MoHO, OTIPM as being too general. These models have been our primary knowledge base for a lot of years without a lot of development. There is an ontological absence in these diagrammatic presentations of occupation with an oversimplified structure. Where an individualistic, static way of understanding occupation is described instead of the real-life lived experience of occupation. This is the very thing that Kirsh warns us about.

What approach serves disadvantaged, marginalized, and addicted populations best?

(Based on Jacobs own research – theoretical lens is John Dewey’s theory of transaction and inquiry)

Jacob introduces two terms: interactionalism and transactionalism.

Interactionalism is related to terms such as structuralism, dualism, and pluralism – where the person receives feedback from their occupational engagement in that situation, but the general structure is created by the persons experience in a linear fashion. Instead, the transactional perspective describes the external world as an essential premise of our existence as humans (not fixed and stable as these structures constantly change). Human activity is therefore situated – we try to make sense of phenomena in an always emergent world in an attempt to obtain stability, and through practical application of our knowledge we can establish passing stability in given situations. Jacob relates this to the case of Bjarne – a person who has not yet found the knowledge to create stability in his life.

Jacob goes on to say that instead of looking at occupational performance – we need to look at how human action is situated – as we change our way of engaging in response to a particular situation. The disadvantaged, marginalize people that we wish to help might be in an unstable situation, without having the knowledge of how engage to create moments of stability. This knowledge is effective action, it is doing.

So, is there a transformative function of engagement in occupation?

Situations: Either indeterminate or determinate.

- Indeterminate situation: open to inquiry – its constituents are not coherent whole, and therefore, shape a problematic nature.

- Determinate situation: Is closed and unproblematic.

Human life: About bringing stability and from to its incompleteness (making an indeterminate situation into a determinate situation).

Human need: A need to constantly test and alter one’s perception of the truth through inquiry – what we know is what we do.

Hence, experimental action becomes a way of overcoming any problem in everyday life.

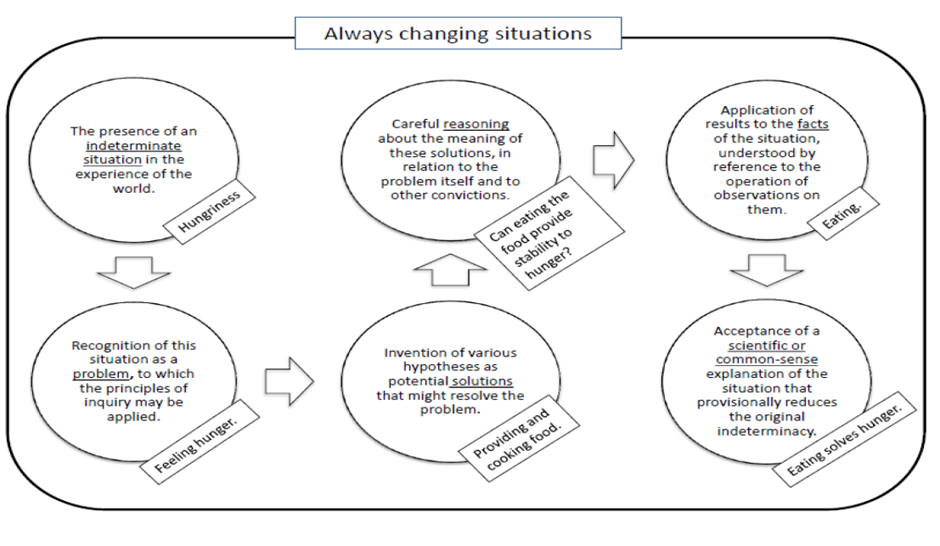

To illustrate this, Jacob introduces a figure that shows the pattern of inquiry.

A short description to support the above model:

- Recognizing the hunger (an unstable indeterminate situation)

- Applying existing knowledge to that situation

- Applying a hypothesis on how to solve that problem

- Carefully reasoning out the possibilities

- Through engagement in occupation – the hypothesis can be applied into a way of acting. To see if a more stable situation can be established

Again, as mentioned before, some people are not able to apply any kind of knowledge on how to make an indeterminate situation into a determinate situation.

Bjarne who was mentioned earlier- constantly being on the couch is in various indeterminate situations. He does not know how to act to change that. For change to happen Bjarne needs help from an Occupational Therapist – who does not only focus on Bjarne’s occupational performance but also on Bjarne’s knowledge on the occupations he is supposed to act upon. And why is that? Because his problem is not his occupational performance but his lack of knowledge to apply in the situation.

Guiding principles on how to help people make indeterminate situations into determinate situations:

- Motivate them

- Give time (more time to benefit, to understand and to explain various things)

- Making individual assessments of the citizen’s resources (how do they tackle their situation, what knowledge about being in their situation do you have?)

- Think of ourselves as health representatives and not only has professionals helping people with their everyday life

- Focus on improving their self-efficacy

- With situational problems we need to think about interprofessionalism

- Strengthening individuals by focusing on citizen rights

Social Occupational Therapy – a socially and politically responsible discipline

What is Social Occupational Therapy? It refers to politically and ethically framed professional actions that target individuals, groups, or systems to enable justice and social rights for people who are disadvantaged by current social conditions.

Jacob’s conclusion

There is a call for a more socially and politically responsible discipline where we adopt a broader situated and sociopolitical approach. There is also a need for more empirical research and a need for a discussion of whether our professional language model (and methods) allows us to become a socially and politically responsible discipline.

Jacob believes that within the next 5-10 years, the focus of occupational therapy will be more towards the situation rather than the performance of occupation.

Questions asked at the end of the SPOTinar:

(Q) Do you suggest that Occupational Therapists (or atleast researchers) should become part-time philosophers if we are to take an ontological perspective? And how might a normal occupational therapist do that without asking existential questions that might be difficult to ask oneself? I guess the question is, how do we do this as occupational therapists in a responsible way? Should researchers take the mantle and create theories for the general population and therefore the responsibility is on the researchers?

(A) Pragmatism is only one way of understanding – there are a lot of different philosophical ideas that we can apply in various ways. It is not about being part time philosophers. Teachers have the job to introduce students to different philosophies and what understanding that gives in relation to our profession. Like this presentation being a way to introduce a philosophy into our understanding of occupation. As future occupational therapists – we should do the same if we find a theory interesting.

[1] Whiteford, G & Pereira, R. (2012). Occupation, inclusion and participation. In G. Whiteford & C. Hocking (Eds.) Occupational Science: Society, Inclusion and Participation pp.187-207. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

[2] Morville, a. Larsen, A (2017) Occupational justice – at fremme retten til aktiviteter. I Nordisk aktivitetsvidenskab. S .193 –213

[3] Stadnyk, R., Townsend, E., & Wilcock, A. (2010). Occupational justice. In C. H. Christiansen & E. A. Townsend (Eds.), Introduction to occupation: The art and science of living (2nd ed., pp. 329–358). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

[4] Whiteford, G. (2010). When people cannot participate occupational deprivation. In C.H. Christiansen & E.A. Townsend (Eds.) Introduction to occupation: the art and science of living Second Edition. (pp.303-328) Upper Saddle Creek, NJ: Prentice Hall.

[5] Hocking, C. (2017). Occupational justice as social justice: The moral claim for inclusion. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(1), 29-42

[6] Stadnyk, R., Townsend, E., & Wilcock, A. (2010). Occupational justice. In C. H. Christiansen & E. A. Townsend (Eds.), Introduction to occupation: The art and science of living (2nd ed., pp. 329–358). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

[7] Hocking, C. (2017). Occupational justice as social justice: The moral claim for inclusion. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(1), 29-42